human aesthetics after AI

What happens to humans and human art in a world of AI is something people talk about and debate all the time, often saying the same things. For instance, many have observed — even before the advent of mainstream AI — that with new technology cycles and new machines, we see a return to artisanship: rough-hewn, handmade, small-batch craft.

This can be referred to as the “William Morris effect” — see Krzysztof Pelc here — Morris was considered a dominant figure in the Arts and Craft movement, which was partly a reaction to industrialization in the late 1800s/ early 1900s. [Morris actually came to the Arts and Craft movement about 5 years later from it’s more formal founding, but was very influential in it.] Pelc asks, “Why would people derive more aesthetic pleasure from an otherwise identical illustration, painting, or poem, merely because of how it was made, or by whom? It’s one of the distinctive quirks of modernity.” He shares some thoughts (and some research findings) on that question — including the question of “fakes” — in the article linked above.

What I’m interested in here, though, is something else: Not how AI changes appreciation for human art, but: How do humans change their aesthetics in a world of AI? One of the best riffs I’ve seen in science-fiction here was in book three of the Three-Body Problem trilogy, Death’s End, where Cixin Liu explored the interplay of culture and tech across several generations. There, he focused more on gender as the aesthetic. Here, I’ll focus on human voice and human beauty — as illustrated by two recent examples I came across and that brought this question top of mind for me:

1) Humans are still narrating audio books… but they sound so much like machines

Whenever I’ve worked on a book project being converted to audiobook, podcast ad read by a a host or some other producer, or other audio, I’ve been struck by how so many of the voices — all human actors/ narrators! — sound AI-generated. Given how much AI voice technology has evolved, of course it’s reasonable to immediately wonder, but wait, *is* this AI?? But in most cases, it is not.

Take for example the narrator of this new biography of Anne of Green Gables author Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Gift of Wing. You can listen to a sample here (you don’t have to be an Audible member; just click on the headphones icon next to ‘preview’ and listen to 30 seconds or 3 minutes of the 30-minute introduction):

https://www.audible.com/pd/Lucy-Maud-Montgomery-Audiobook/B0DTV6HJFG

Do you hear what I mean?

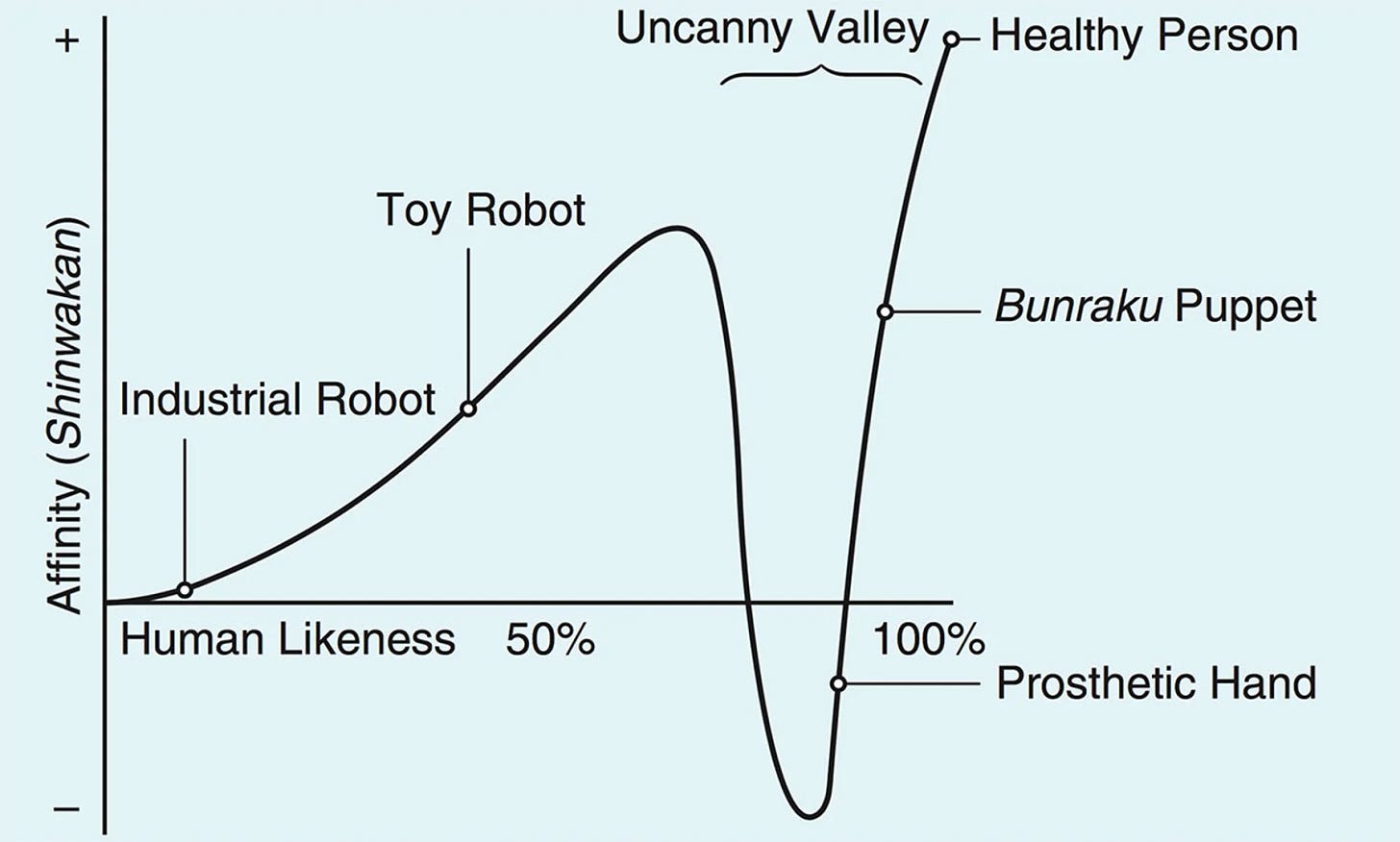

No, I’m not talking about the uncanny valley effect here; it’s the opposite effect, or at least, in the opposite direction. [By the way: You can read the original essay on the uncanny valley by Masahiro Mori, who coined the term in the context of robotics, in its first authorized English translation, here. In meantime, here is a graph from IEEE Spectrum illustrating the phenomenon — and to be clear, the phenomenon hasn’t been tested rigorously; it is more an observation-by-intuition or illustration-by- example:]

So, the audiobook sample I shared above isn’t really an uncanny effect.

Yet why does human voice have to sound machine-like, tinny, and flat like AI at all? Especially when voice-AI is getting so good that it sounds nearly* as good as human voices? (*Accents and cadence are still hard.) Have modern voice actors not caught up; is no editor monitoring the quality of audiobook auditions; or is it perhaps intentional, some effort to sound neutrally mechanical? If you bring “the Morris Effect” to this, you’d expect human voices to work much harder to sound much less like machines…

I haven’t listened to all the voices in Audible’s Narrator Hall of Fame to see if the top-rated voices at least resist this AI-sounding effect. But I do read a lot of audiobooks — and lately I’ve been opting only for the ones read by established actors, as they are the most humanly performed in cadence, pace, and variety. [The best by far has been Thandiwe Newton (yes!) reading Jane Eyre — excellence beyond measure. More on that in a later edition.]

#2) We’re seeing the advent of “aliengelic”, machined- glass skin beauty

Makeup artist Pat McGrath apparently coined the term “aliengelic” with her LUST: Gloss lip gloss line. Combined with the face makeup she did for Margiela’s Artisanal [emphasis mine! the irony!] Collection 2024 as directed by John Galliano, you can see what “aliengelic beauty” looks like below (watch the whole show, or rapidly slide through to find a few face-closeups):

It’s almost a machine-like beauty... like machined glass. [By the way, one of my favorite pieces of tech writing to this day is my former colleague Bryan Gardiner on Corning creating new glass in Wired 2012.]

Again, this is not AI borrowing human features, but in the other direction: Humans borrowing from AI (more precisely, robotics) — what you’d expect humanoid skin to look like. It’s not quite caricaturing human features, either, like we see with anime. Nor is it fairycore or elfore. It’s simply… glass-like.

In an essay for Vogue, where Lena Dunham commented on the trend of “glass skin”, McGrath shared that the look was likely influenced at an early age by watching her mother do a full face of makeup, and then sit in a warm bath. Because makeup material/ technology back then was overly matte and powdery, doing so was one way to get a dewy finish.

Glass skin takes the concept of “dewy” skin much further. McGrath said that the look was “deeply rooted in the allure of 1930s porcelain dolls”. [Materially, 1930s “composition” dolls were often manufactured from: cornstarch, glue, resin, sawdust, and/or wood flour; I listed the materials here alphabetically, not in order of use, as I didn’t research the proportions in the composites.]

So what does porcelain-“skin glass”, “aliengelic beauty” look like close up? Here’s one YouTube short remixing the look in vertical video form; I’ve also shared a screengrab from it below:

As you can see here, the skin has an almost alien, AI-like beauty.

I wonder if we’ll see more or less of this kind of thing moving forward.

~sonal

artdev is a newsletter all about aesthetics and arts, beauty and building, craft (not crafts!); curating and connecting interestingness across different worlds; plus cultivating taste (can it be trained? where? how?)

p.s. You’re getting this if you subscribed to any of my previous newsletter lists over the past few years — as this is my newsletter combining all of those themes, revamped; more on that vamping here: why, what it’s about, what to expect, and more. Feel free to share this with others!

One of the more celebrated albums of 2024 was Mk.Gee's Two Star and the Dream Police. It's a very good album, if you haven't heard it definitely give it a listen. On one hand, it's pulling from a lot of well-known sources (like Fleetwood Mac, The Police, Prince) but on the other hand there are some truly bizarre sound choices in there. The guitars are all tuned several steps lower than usual, there's a reverb that only kicks in at higher volumes, etc. etc. The live performances on YouTube crank the weirdness up even more, with guitar noises that border on pure static. The lyrics are perfectly calibrated weirdness too.

He's a growing force at every level of the music world. He was recently credited on the Bon Iver album, and his subreddit is chock-full of people copying his sound.

I think a lot of his influence and success is explained by a desire to sound very distinct and obscure. Mk.Gee explicitly says this in an interview. At around 5:20 in this BBC show (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DuW16YUG9rk), he says people put too much effort into making music seem human!

Apparently there's also a fashion show that used his live performance for the walk:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEIhBHjtEos

Those glassy-skinned models and robot-voiced narrators you highlight, show us eagerly adopting machine aesthetics as our new ideal, just like we tried in the 70s with Kraftwerk's robotic personas, sci-fi chrome bodies, and synthesised disco vocals. LLMs are merely the evolutionary apex of our shared blandness, and so the scary part isn't machines becoming human, but how willingly we're becoming insipidly machine-like, our creative posturing concealing nothing but emptiness.